Revisiting “Amelia & Friends,” Oakland

My 4,000 square foot studio was totally dark as I turned on a projector, illuminating 35 linear feet of canvas, primed and stretched on the wall. On the glass of the projector, I’d placed the first of three transpariencies, sketches of aviation pioneers that flew in and out of California between 1920 and 1940. I’d spent six obsessed months racing up and down California to research just which significant fliers should be included. There were 30, including Amelia Earhart. My intention was to metaphorically reincarnate these characters, and gather them all together, though they’d never actually all been together at one place and time. Six months interviewing biographers, aviation museum experts, and even Earhart’s last official photographer. I’d read countless books about Earhart, and articles about the others.

Just as the blank canvas came to life, breaking news came over the radio, announcing that what was believed to be the sole of Earhart’s shoe had just been discovered. I froze. It was if I was actually channeling these heroic aviators, and this was a sign.

This is how the story started, in 1991. (To see update, scroll to bottom.)

In a Hilton Hotel near the Oakland Airport at a restaurant called “Amelia’s,” a tiny, yellow toy plane hung in the doorway, the only reference to the pioneer aviator. This was amazing because she, like so many others, had flown in and out of Oakland. I had a budget. It was up to me how I wanted to spend it, and often my efforts far exceed what was allocated. I decided that I had to create life-sized portraits of the pioneers of aviation who had flown in California between 1920 and 1940.

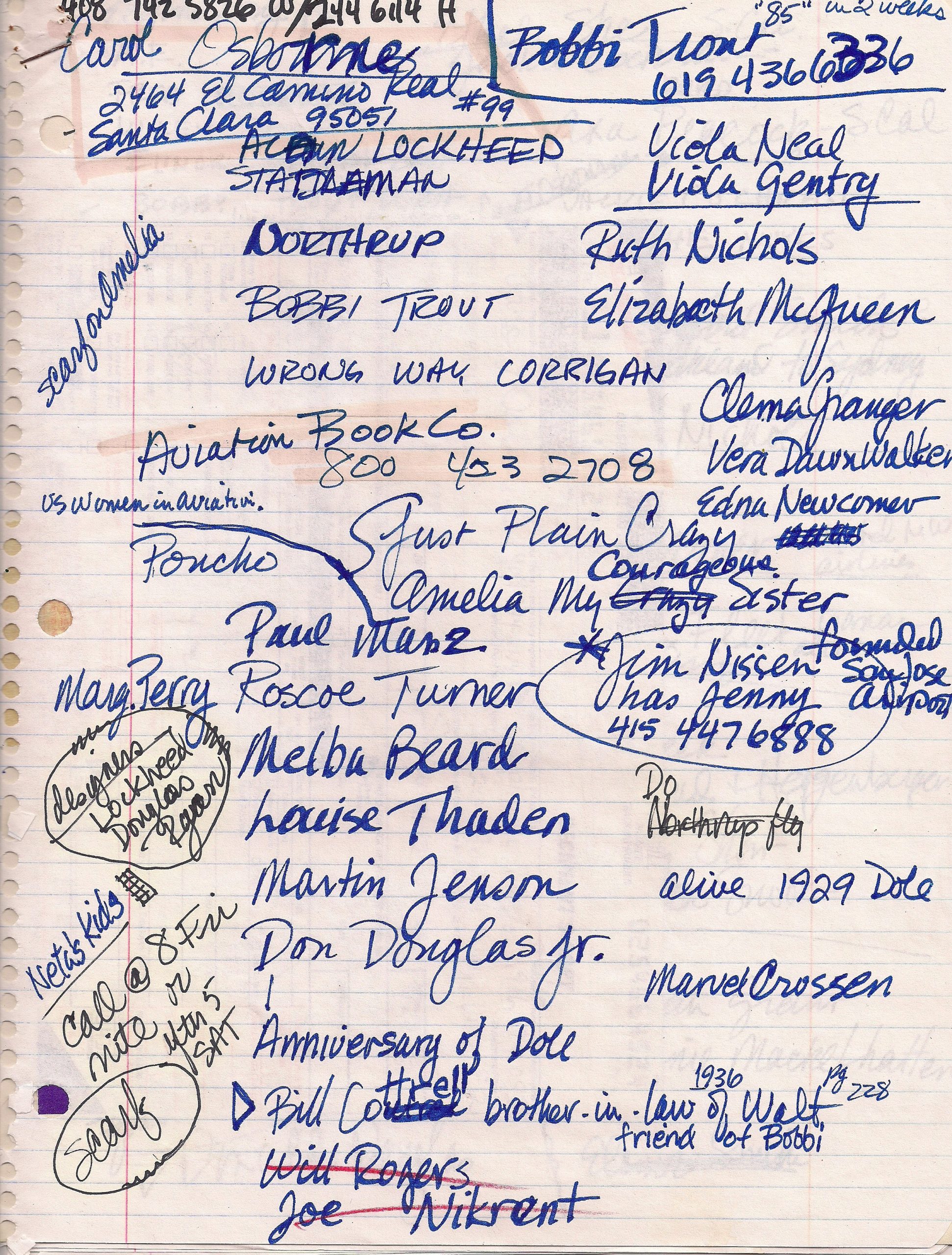

I wanted to gather them all together for the first time, as if they were sitting just outside a window, looking into the restaurant from the tarmac. First, I had to find out who had flown in California during that time. There was no one source for this effort. This became an obsession and I spent more than six months traveling up and down California doing research.

Next, I had to pick who I thought were the most significant, most interesting characters. This was subjective on my part, but it required that I do a lot of reading and spend a lot of time talking to museum curators and other scholars. I formed a temporary friendship with one of Amelia’s biographers, Carol Osbourne. I found and met a man who claimed to be her last “official” photographer, Albert Bresnick, an elderly charmer. He gave me a portrait of her, signed by him. He also said that he thought Earhart might have been pregnant on that last flight. But Earhart was only one of thirty that I eventually portrayed, including Charles and Anne Lindbergh and Wiley Post and a surprising number of female heroes.

My studio was a concrete tilt-up that was searing in the summer and freezing in the winter. It was so large that I often rolled around on my skates. On the longest wall, I had stretched and primed a single piece of canvas, 5’ high by 35’ long. Primed canvas is always so beautiful, pristine and pure that I’m often reluctant to destroy its pristine purity with a painting. This canvas sat vacant for several weeks as I finished my research and finalized sketches. I kept finding fascinating bits of information and it was so hard to limit the number of pilots so I could fit them all in. Finally, the day arrived when I was to actually start projecting and drawing the images on the canvas.

Literally, at the moment that I started to draw, this news flash announced that a relic possibly belonging to Earhart had just been found. I froze, shocked at the coincidence of the timing. I thought that perhaps there was a reason I had chosen this project and to this day, I still wonder.

I believe at least one of the murals is still installed. Others are in storage, with the promise of donating them to an aviation museum in California.

February 2021. My first visit to the Aerospace Museum of California, to meet the director, Commander Tom Jones, US Navy, retired. If we can acquire the murals, all three would be installed above the green wall, where the 48-star flag now hangs. I would also like to add a few more aviation heroes, from WW2, for example, and several amazing test pilots. The murals at the Hilton totaled about 35 linear feet, 5 feet high. The available space is 50 feet. In this picture, a portion of the largest kite in the world (maybe there are newer versions by now) was donated by Google. Its purpose is to fly in circles, tethered to an electrical hub, to generate power. This amazing museum is an affiliate of the Smithsonian.